The Great Smoky Mountain Journal

Source: Fox News

Posted: Tuesday, January 01, 2019 02:30 PM

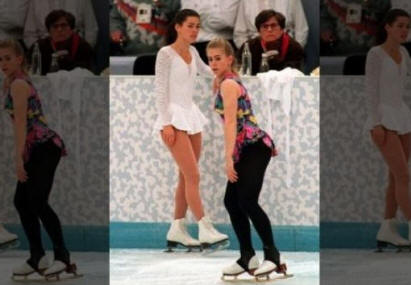

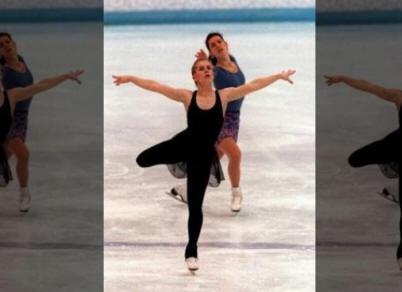

Former DA In Oregon: Disgraced Skater Tonya Harding "Involved Up To Her Neck Right From Day One" On Kerrigan Attack

Norman Frink, a former Multnomah County district attorney who headed the

investigation into Harding's alleged involvement with the attack, told

People the disgraced skater was involved in the suspicious attack on

Kerrigan despite her claims she was not.

"[Harding] was involved up to her neck right from day one," Frink

alleged.

Kerrigan was hit in the knee with a police baton just seven weeks before

the 1994 Winter Olympics. Shane Stant was later identified as the man

who clubbed Kerrigan in the knee as the ice skater walked off the rink

from practice on Jan. 6, 1994. The plot was set up by Harding’s

ex-husband Jeff Gillooly, Brian Sean Griffith and Derrick Smith.

Gillooly and Griffith pleaded guilty to “racketeering” in connection

with the attack. Harding’s ex-husband was forced to pay $100,000 and was

sentenced to two years in prison. Griffith, Smith and Stant were each

sentenced to 18 months in prison.

For years, Harding has claimed she was not involved in the attack that

injured Kerrigan but did not keep her from competing in the Olympic

Games. Kerrigan won a silver medal for her skating performances while

Harding did not qualify for any medals.

Gillooly told FBI agents Harding called for the attack. FBI documents

stated Gillooly alleged he told Harding in December 1993 that “we should

go for it (the attack).”

“Okay, let’s do it,” Harding allegedly

said.

A significant piece of evidence backed up Gillooly’s statement: a

handwritten note reportedly written by Harding stating where Kerrigan

would be practicing.

The 2017 film “I, Tonya” which centered around the scandal, showed

Margot Robbie, who portrayed Harding in the film, asking the judge to

put her in jail instead of banning her from ice skating.

However, Frink said that was not accurate.

“She could have gone to prison instead if she wanted to. This is what

she wanted to do at the time,” Frink told People. “We would have gladly

accepted an alternative sentence where she got the same as everyone

else. There’s no point in her whining about the choices she made back

then now.”

Frink said Harding did not receive jail time because of the lack of

evidence.

“The only reason she didn’t go to prison with the other people, although

the quality of evidence was good, it wasn’t as good as the other

people,” Frink said. “We made a decision, as you do often in criminal

cases when you don’t have iron-clad evidence, we made a compromise.”

Frink said he has not seen the Academy Award-nominated film but saw

Harding in ABC’s “Truth and Lies” special where the ice skater admitted

on air that she “knew something was up.”

Harding told ABC she did not tell Gillooly to go through with the attack

despite his testimony but she alleged she “overheard” the men talking

about “how maybe we should take somebody out so we can make sure she

gets on the team.”

“I go, ‘what the hell are you talking about?'” Harding alleged.

“It was a startling admission, because it was the first time she ever

admitted something that gets closer to the truth than what she usually

says,” Frink said. “With Tonya Harding, the line between truth and

fiction is always blurry.”

In March 1994, Harding pleaded guilty to “conspiracy to hinder

prosecution” - meaning she “knew who had done the attack but only

afterward and she didn’t report it immediately” - and was sentenced to

three years of probation, 500 hours of community service and was forced

to pay a $160,000 fine, The New York Times reported. She was banned for

life from the U.S. Figure Skating Association in June 1994, Cosmopolitan

reported.

In an interview with The New York Times that was published in January

2018, Harding told the paper she knew the attack would follow her for

the rest of her life.

I knew that this would be with me for the rest of my life,” Harding

said.